in a (once-)blossomed place

Album Review

By Forest Muran

(Cover art by Yaz Lancaster)

(Cover art by Yaz Lancaster)

Almost a year ago, I reviewed Sebastian Zel's electroacoustic EP findings, released through the New York based record label people places records. Continuing in the tradition of entirely lowercase titles, people places records has, on July 26th, come out with their first release of 2019, titled in a (once-)blossomed place. This album features four lengthy tracks, divided between American composers Cassie Wieland and Erich Barganier, and seems to be the first of a new series of releases by people places records which intends to feature albums created by composer pairs. This first pairing already has blossomed into an intruiging set of musical works, and I want to try and unpack some of the ideas that have sprouted from them as best I can.

Reflecting the title of the album, the first piece already throws us into an abstract world lacking in vegetation. In contrast to the other works on the album, Strange objects, by Cassie Wieland, does not feature any performed, acoustic instruments. Instead, it presents us with the mechanized timbral world of electronic music. Nevertheless, in spite of its artificial musical materials, this composition features a rather organic additive form, much like the movement of a wave. First, a somber, sustained synth pedal awakens us to an ambiguous tonal space, later churning our initially calm disposition with dissonant pitch phasing and sweeping mechanical scratches. The sounds continue to aggregate, adding various unplaceable sampled sounds, until finally, after a climactic moment, or a series of moments, we are left again with the tranquil stillness of a hollow synth pad, this time punctuated by clicking, clock-like samples.

The album's description states that Wieland's pieces intend to “present the composer’s take on object/environment displacement.” While at a literal level, the concept of displacement deals simply with the transference of an object from one physical location to another, perhaps the current interest in it stems more from a kind of cultural or existential displacement, where we feel disconnected from our origins, from society, or from the very idea of existence. The idea of displacement of course suggests that things, in fact, have a natural home where they actually belong, and if only we could arrange things in their right places, all could be resolved. Perhaps in the abstract, harmonic world of perfect cadences and harmonic resolutions such an ideal is possible. But in our own unstable world, the state of displacement seems to be our actual home.

Music, for instance, is always in a state of displacement, particularly computer music. This is the fundamental distinction behind the electronic / acoustic dichotomy, after all: Acoustic music is produced by an existing body, while electronic music is ghostly and disembodied. But if we are to look at the acoustic phenomenon more closely, we can see how arbitrary the comparison is. We are very insistent on protecting the idea of the authenticity of our senses. But whether you have heard Beethoven's 9th Symphony played by an orchestra in real time, or whether you have merely heard an audio recording of it on YouTube, the end experience, for the mind, is still “having heard Beethoven's 9th Symphony.” The difference of course lies in the body, which prefers satisfaction over mere perception. In any case, the very process of receiving an organized impression from the great, tangled jungle of reality, reflects a kind of displacement. Regardless of how the sound reaches us, it must first be displaced before it is processed.

(Displaced object photo by Forest Muran)

(Displaced object photo by Forest Muran)

What does it mean for Wieland's piece to be concerned with displacement? The piece of course features a variety of sound samples which seem to derive from field recordings of various objects. That said, it is difficult to tell what the original objects used were. In a very Heideggerian sense, Wieland's objects have become strange, and displaced from their original source. In their abstractness, even Wieland's acoustic material takes on a synthetic quality, since they can no longer be connected with the bodies which created them. This is a idea which is explored deeper as the album continues. In listening to Strange objects, Wieland's piece has itself become a strange object, being displaced from its mysterious origin as a recording on a computer hard drive, and entering into our phenomenal experience. Not only the originally sampled objects, but the digital recording itself are displaced in our abstract experience of them.

Weeds, also by Wieland, is an entirely acoustic work, performed by the Line Upon Line Percussion ensemble. Unlike the first piece, this more organic work has a more popular tone, featuring a contemplative vibraphone melody, and a musical structure that it wouldn't be surprising to find on an early 2000s Warp Records release. As with the first track, Weeds features an additive structure, with its elements gradually being developed and stacked upon one another – a technique very much in vogue for the movie music-influenced composers of today. The technique differences greatly from the classical tradition, and even from the familiar verse-chorus structures of popular songs. I wonder if a connection could be made between it and the music of Bach or Lully, in that it perhaps reflects a kind of earnest faith in the reality of human affect? In this vein, Weeds begins in a very gentle sound environment of percussive brushes, which is soon punctuated by resonant points played on the vibraphone. Eventually, a relatively stable drum kit enters the mix, and the music takes on a syncopated, jazz-like tone, albeit in a rather complicated rhythmic scheme. In this track, it's something of a relief to be presented with sounds which we can trace to a definite body. For a moment, we are given relief from the displaced abstraction which characterized much of in a (once-)blossomed place.

A weed is generally considered to be something unwanted. When spotted, we pluck them from our gardens. At least to our ego-centric perspectives, a weed is a very alien object, a strange object, which must be dealt with accordingly. If we are to look beyond our own interests as gardeners for a moment, however, we might be able to see the weed in a different light. Perhaps it is not a displaced object after all. Perhaps it is not an object that has strayed far from its proper home in the natural world (the part of the natural world that is not our backyard), to rear its unwanted stems on our property? Indeed, an object can only be displaced, if it is be wrongly placed. But the unknowable jungle of reality does not function in terms of what belongs where. Beyond subjectivity, the environment is indeed irreducible from the objects found within it. The illusion of the acoustic percussion sounds we hear projected from our computer speakers, for example, can on one level be seen as a kind of displacement, but on another level, the digital sound coming through our speakers is exactly where it belongs. The very act of listening is a displacement, and even when we are faced with acoustic sounds, the acoustic phenomenon itself inevitably involves an abstraction of sound from its source. Music is inherently alien to its objects.

(Unwanted object plus vegitation photo by Forest Muran)

(Unwanted object plus vegitation photo by Forest Muran)

The third piece on the album takes us deeper into the heart of reality, as we flow down this river of reproduced sound. At least according to the piece's title, The Veneer Melts, by Erich Barganier, it would seem that we are getting closer to the true state of things. According to the album description, Barganier also “is guided by ideas of displacement.” Nevertheless, Barganier's inspiration comes far more from the sound world of noise-music, being constituted by a mesh of piercing digital sounds, clusters of portamento violin plucks, and recordings of radio chatter. Throughout the piece we are lead through a series of musical trials, which pop, scrape, and clash, until we reach a coda which reintroduces the background radio chatter. This time, however, the radio chatter begins to speed up under a sardonic counterpoint of pizzicato strings playing what sound like Webernian blues riffs. The entire piece is forceful and fierce, and although the album description mentions an element of anxiety being conveyed in the piece, I would suggest there is also an element of comedy – a very dark kind of comedy, of course, like when we laugh at the absurd lengths Kafka goes to in order to torture his protagonists.

In the same sense as recorded music, the radio carries with it an idea of displacement. The absence of the human body is made all the more distinct through the speeding up of the recording near the end of the work, which draws our attention to the piece's artificial elements. While The Veneer Melts indeed features many acoustic and indexical elements, it nevertheless makes us feel especially removed from them because of their distorted, unnatural treatment. While these objects indeed form their own natural environment, weeds growing in an abstract space, we nevertheless still feel, as human beings, a sense of disconnect with reality when we hear the human voice distorted. Perhaps it's an aesthetic limitation of our minds - or an aesthetic opportunity.

The album description mentions Barganier being influenced by multimedia artist and noise-music composer Ryoji Ikeda. This comparison is interesting, in that it gives us more insight into the relationship between art and displaced objects. A lot of Ikeda's work concerns itself with presenting the human subject with forces of reality that are considered unknowable – things like complex patterns, unimaginable variety, and quantum systems. In this sense, Ikeda's work presents ontic reality through a phenomenal lens, in an attempt to draw attention to the fact that these subjects actually are unknowable. A lot of the effect of his works come from the capacity they have to expose us to the mystery of existence. A large part of that mystery comes from the realization that we are inherently displaced, and that the very structural foundations of existence are alien to our capacity to comprehend – and, in a sense, that this mystery and uncertainty is our true home. That seems to be the appeal of a lot of noise music, as well as this particular piece. When we become overwhelmed by what is strange to us, the veneer of understandable reality begins to fade away. The familiar human voice begins to distort beyond recognition, and we are no longer convinced that there is a distinction between the artificial and the real.

(Real tree turned artificial photograph by Forest Muran)

(Real tree turned artificial photograph by Forest Muran)

The final piece in the album continues to explore the ambiguity between the realm of the electronic and the acoustic. This piece, also written by Barganier, seems to feature a Ukrainian title. Калі Я Адкрыў Вочы, at least according to Google Translate, translates as When I Opened My Eyes. The musical world of this piece suggests an apocalyptic state of horrific awe. Taking advantage of the capacities of digital editing in the best way possible, Barganier takes samples of the flute and piano playing dramatic, forceful gestures, and compounds them over one another to form a massive collusion of sinister sounds. When we open our ears to the force behind the work the effect is beautiful, terrific, and full of wrath.

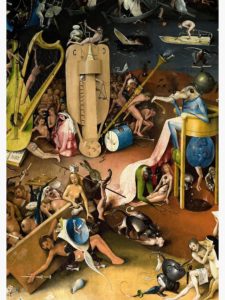

When we think of the divine, the popular image that comes to mind is often peaceful, sometimes involving something like floating clouds, or a golden light. Certainly not something we would associate with, say, the atonal serial music of Arnold Schoenberg. Nevertheless, in an essay I wrote in my first year of university, and which I still stand by to this day, I argued a connection between the serial music of Arnold Schoenberg and the Vishvarupa, or cosmic form of Krishna, found in the Bhagavad Gita. I may as well have been talking about Barganier's piece: “What many call ugliness is really the feeling of shock produced at a confrontation with overwhelming stimuli, be it the cosmic form of Krishna, or the pantonality of Schoenberg's later music.” In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna at one point reveals his universal form, which depicts, at once, all the majesty and terror of creation. Naturally, his audience, the warrior Arjuna, is horrified. To be subjected to so much reality at once is a terrible thing for those not ready for it.

(Detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch)

(Detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch)

What I did not know at the time of my writing that paper, was that Arnold Schoenberg was far more influenced by Balzac than ancient Hindu texts. The result, in any case, was the same. In preparation for writing what was to be his first grand, orchestral symphony, a piece which would later turn into his well-known Die Jakobsleiter, Schoenberg grappled with problems of the divine, and intended to set passages from the books of Psalms in his epic work. Despite his biblical research, Schoenberg's greatest source of inspiration actually came from Honoré Balzac. In Balzac's novel Séraphîta, Schoenberg was captivated by a vision of hell which presented the subject with an ungraspable confusion of the senses, a world of experiential excesses that mundane minds could not process. Balzac describes his vision of hell as a place containing “life that gave no hold to sense, fragrance without odour, melody without sound, no surfaces, no angles, no atmosphere.” It was a terrifying, apocalyptic vision, but it gave Schoenberg a sense of spiritual insight which inspired him to craft the intensely dissonant, yet transcendental Die Jakobsleiter.

As with Schoenberg's spiritually charged vision of hell, Barganier also opens our eyes to a terrifying and overwhelming impression of reality. It is the same strategy employed by Ikeda when aiming to overwhelm his audience with the complexity of the reality beyond our everyday human impressions. Like Ikeda, Barganier's sharp, plunging counterpoint confront us with vast complexities which, although we find them difficult to grasp, force us to adopt a position of apocalyptic awe, a reverence for the destructive powers of reality.

With the release of in a (once-)blossomed place, people places records continues its streak of releasing thoughtful works which bridge the gap between the worlds of classical and popular music. In a musical environment tyrannized by commercial distinctions, it has become difficult to distinguish the music we listen to from the conceptual categories imposed on it by the demands of the market. Nevertheless, the differences between the “classical” tradition and the “popular” tradition are continually breaking down, especially in an environment increasingly becoming more dominated by independent musicians, who often create more based on personal interest rather than sales projections. Labels like people places records are a great benefit to contemporary music in general, and act as a space of reverence for the efforts of their artists as well as a celebration of their ideas.

If you are interested in listening to similar music that is approached in the spirit of breaking free from conceptual frameworks, written by composers familiar enough with those frameworks to know where the exit signs are, I recommend giving a listen to other works in the people places records catalogue. In any case, I look forward to whatever new releases the label might have planned for the rest of 2019.

- Forest Muran

You can listen to and purchase in a (once-)blossomed place here

You can read my article on another people places records release, findings by Sebastian Zel, here

Check out the rest of the people places records catalogue here